In today’s competitive world, companies are always looking for a way to stand out against their competitors. In the past they may have achieved this through features or advertising. More recently organisations have started to differentiate themselves by rethinking the whole customer journey and delivering an amazing experience around all aspects of the product.

We call this “Product-led.” This doesn’t mean that it is “product manager led,” it means that the whole organisation and product is oriented around customer and business success.

Amy Johnson from Propel Ventures led us through 5 steps to bring Product-led thinking into your organisation

What is Product-led?

Product-Led is “a relentless focus on customer value to create products that sustainably drive growth”

When we dig into this a bit more, Product-led is about focus on the value the product creates for your customers and your business. For example this could be in the product pricing, Go To Market activities, or design. This involves having a clear vision and an empowered team to deliver against the vision

Why does Product-led matter?

Product-led is more beneficial to a business as it has a long term growth in mind, as well as minimising waste. Conversely, Sales-led often means only focussing on the next sale, so is not sustainable in the long term. Technology-led means building cool products based on the enabling technology, but risks creating products that don’t solve any problems.

This article will drill into the the 5 core tasks necessary to move to Product-led

- Product Vision

- Product Strategy

- Shared Success Measures

- Organise around value

- Outcome based roadmaps

Let’s dive into each one

Product Vision

A good vision provides clarity on the future, so you know where you are going. This clarity is important because going fast in the wrong direction won’t get you to success.

But you won’t be able to create one by yourself. Vision creation should take in diverse perspectives and different voices to make sure it is clear. Use these voices to focus on the change you want the product to make in the world. You need to find a vision that will inspire the team.

You’ll know when you have a good vision when it is easily internalised by the whole team.

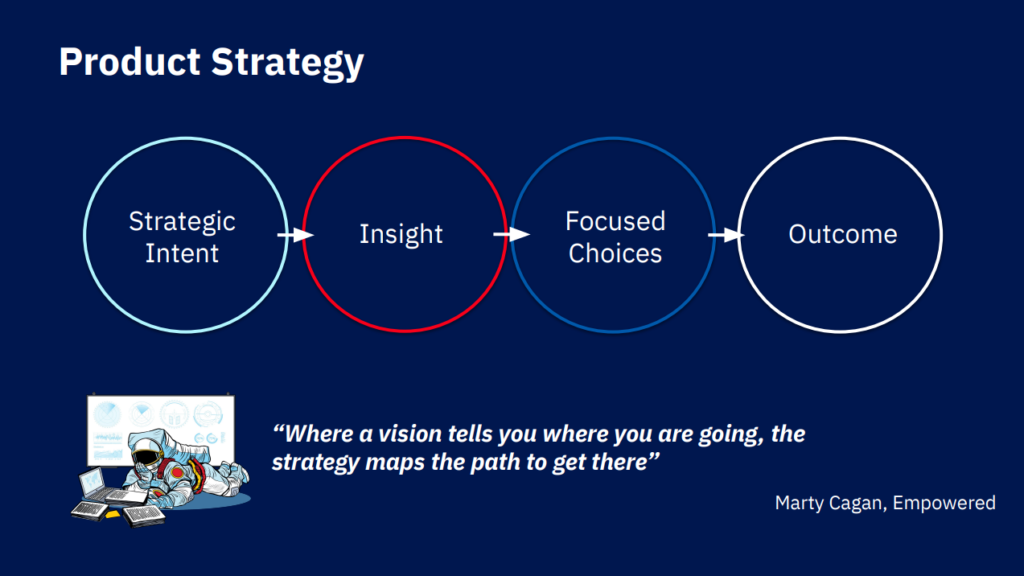

Product Strategy

Product strategy is about mapping out the path to get the product vision. This requires understanding the strategic intent, the challenges and the business goals. Use this knowledge to then clearly articulate the goals, which are prioritised based on strategic intent.

There is a risk in skipping this thinking if you join an organisation. You may inherit everything that is already going on. While it is possible to artificially create a bottom-up strategy by reviewing the backlog and package it into themes, there is a risk that it does not achieve business goals. It is important to make sure your strategy is aligned with the product vision above.

Focus is a key part of delivering against the strategy and vision, so clearly articulate the goals and ensure all activities are targeted towards business goals

Shared Success Measures

Having clear success metrics that are shared helps the organisation achieve alignment, by describing what “good looks like.” It is important that these are legitimate measures of success based on customer value, rather than metrics that might be easy to measure but won’t help you know more if you are on track – known as “vanity metrics.”

Ideally these success measure should be outcomes, not outputs. Outcomes are what the business needs to achieve, whereas an output is a delivery that contribute towards achieving that outcome. For example, the customer cares about how you have saved their time and money, rather than whether you released a feature or not.

To create these success measures, you’ll need to know what is valuable to the customer, as well as a way to measure it. Finding a way to know what good looks like in the product can ensure you are tracking towards a common idea of success.

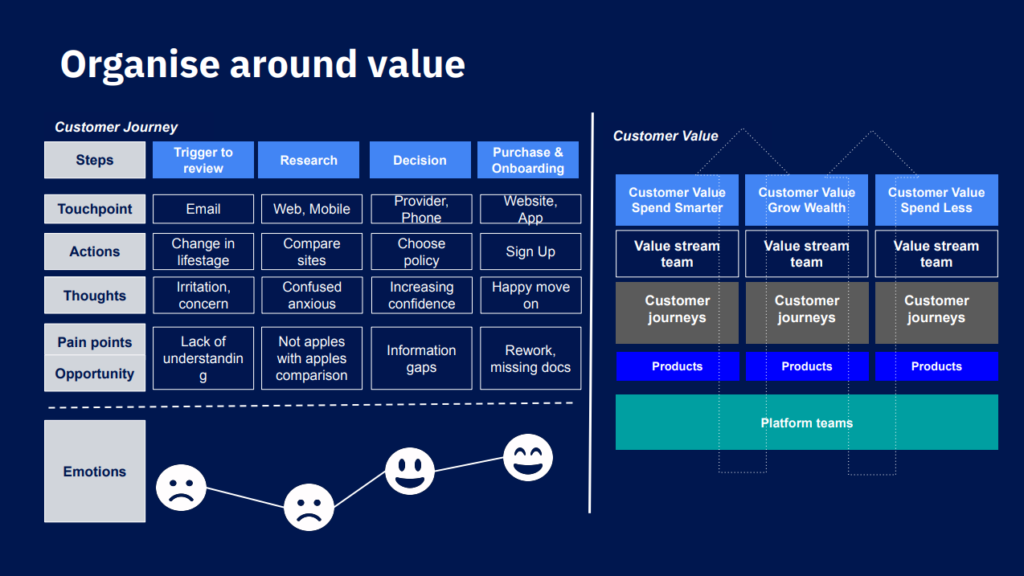

Organise around value

There is a risk in organisational design that you create teams around what the company values rather than what the customer values. This is known as Conway’s Law – where complicated products end up looking like the organisational structure.

To ensure the customer gets the most value out of the product, the company should be organised around the customer’s perception of value with the product. Create a journey map to understand the customer experience, pain points, opportunities and make sure the end-to-end experience works. From there you can define the problem to solve and the metrics of success. Once you have these you can experiment and iterate.

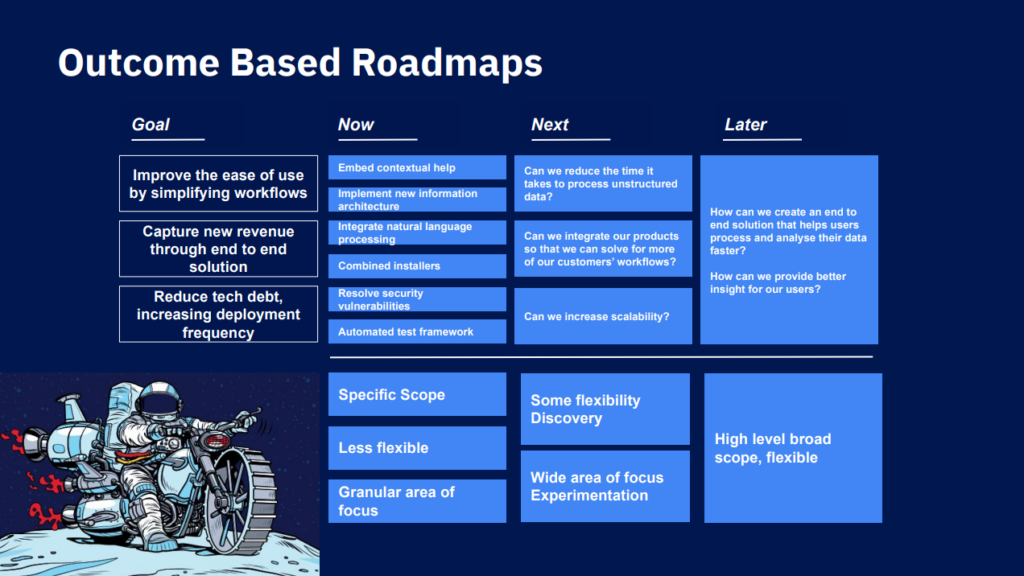

Outcome based roadmaps

Once you know where you are going, how you are going to get there, metrics to measure customer outcomes, and what the customer values, then you need to ensure that delivery stays on target.

An ‘outcome-based roadmap’ takes what is known about how the customer or business measures success, and gives context to every item on the roadmap. It articulate goals and what you are trying to achieve. It also reiterates the product strategy and makes sure that unnecessary items don’t appear on the roadmap.

This makes the roadmap a communication tool, not a project plan. One way to enforce this thinking is to use the now : next : later format. This is a more realistic view given that development is not always predictable, and it allows flexibility to change based on customer feedback

Summary

Product-led is the way to focus the organisation on success; through identifying customer value and sustainable business growth.

There are 5 key areas that need to be consider to successfully make the transition:

- Product Vision – A phrase that describes the future to align and inspire the organisation

- Product Strategy – This maps out the focused path towards the vision

- Shared Success Measures – Aligns the organisation and tell you if the strategy is working

- Organise around Value – Ensure that you are aligned to clear customer value

- Outcome Based Roadmap – Ensure that delivery stays on target

About our speaker

Amy is a product leader, passionate about empowering teams and fostering inclusion. Multi industry experience, now leading the product team at Propel, who partner with you to accelerate your product development and achieve product market fit faster.

Thank you

Thanks to our wonderful friends at Everest Engineering who hosted the event.

And here’s a bit of behind the scenes setup action via Bryce’s tweet

Slides and Additional Resources

https://www.propelventures.com.au/how-to-become-product-led

Thank you